Consider The Whole

Why software engineering is difficult: switching perspectives and choosing the right abstractions.

TL;DR

Engineering is hard because you must constantly switch between detail and big-picture thinking. I learned this when my ‘clever’ component-level loading solution ignored user experience and data dependencies—sometimes the elegant technical solution isn’t the right one for the whole system.

This is another lesson in how to be a better engineer. Engineering, as a sport and discipline, is tough, real tough. It requires you to constantly reorient yourself with respect to the problem you are trying to solve, and how you are trying to solve it.

Because engineering requires a constant, deliberate, switching of frames of reference (or hats, or lens), it is easy to lose where you are at any one point. There is always a picture or vantage point you are viewing. You have to constantly shift between frames, trading the small for the medium, the medium for the big picture. The need to constantly adapt your frame of reference feels more telescopic—forever refocusing—rather than slow and neat. It is easy to get confused and lost. And, when you are lost, your effort is without purpose, your travel without direction. What makes this harder is that these frames of reference have their own internal frames of reference. These views exist at both detailed and broad levels.

For example, implementation details are usually small picture because they require detailed focus. But there’s also a big picture aspect to them. In implementation details, the small picture is at the function or block level, while the big picture is at the application level.

I recently had a lesson in not considering the big(ger) picture during implementation. The experience was similar to what I put down in Systems, Business Requirements, Black Boxes.

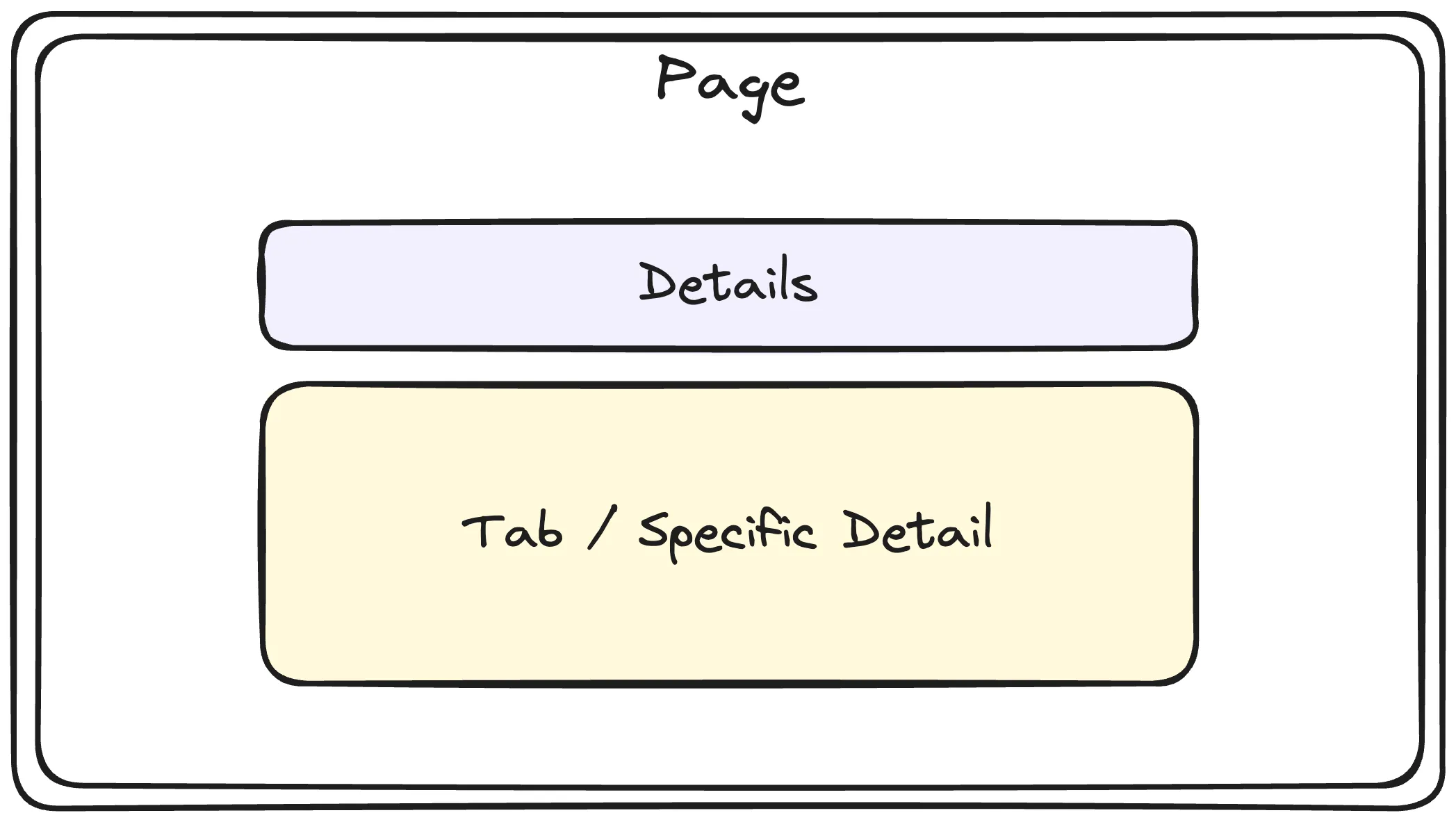

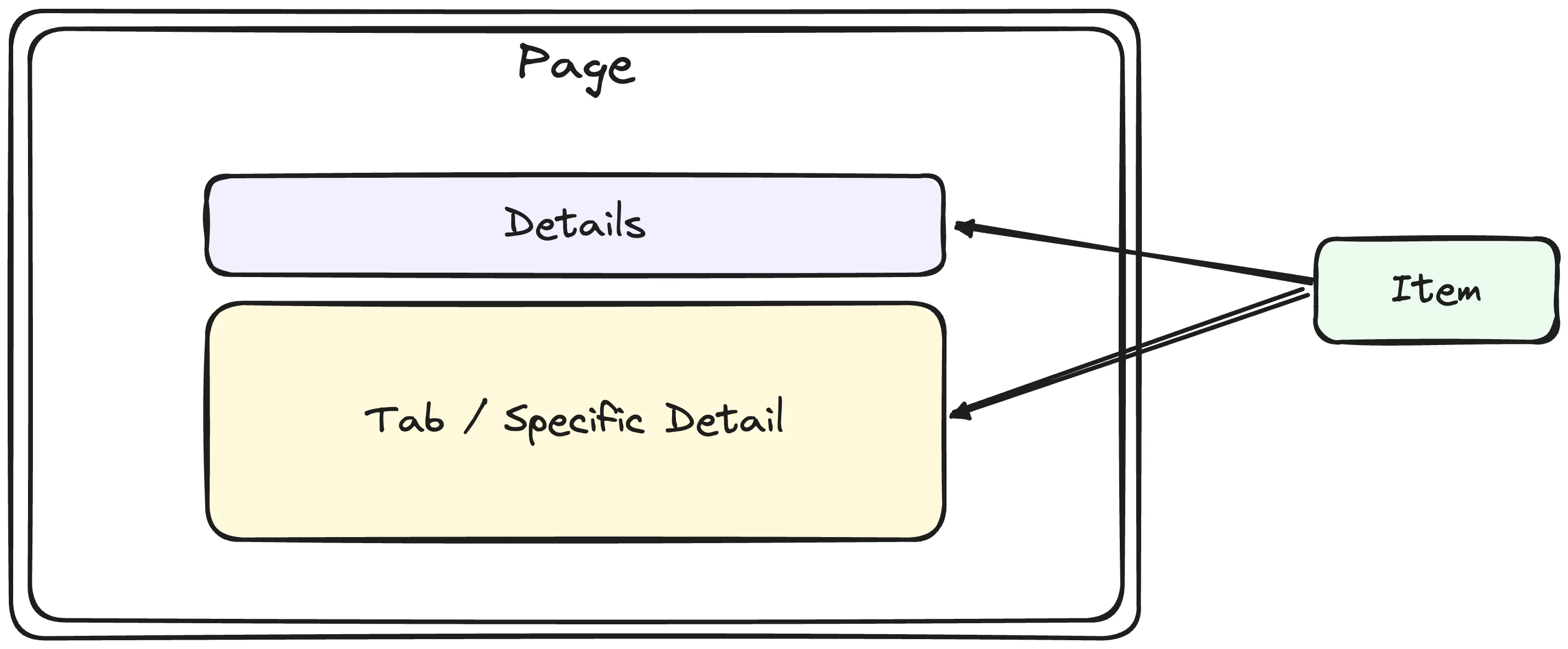

I had a page that was showing an item. It showed both the ostensible details of the item and had tabs containing more advanced, manageable aspects of it.

In my initial implementation, I opted for component-level loading and error handling. Each component—Details and Tab/Specific Detail—managed its own data fetching independently. This follows a reduced coupling pattern: render what successfully meets its data requirements, fail gracefully for what doesn’t. It’s anti-fragile by design: render what we can, discard what we can’t, never crash the entire application because one piece fails to load. I’ve always favoured this approach. It mirrors progressive enhancement principles and feels more resilient. The logic is sound: why take down the entire application when only a subset fails?

But implementing this pattern requires deeper consideration than “it’s elegant and resilient.” This thinking veers dangerously close to the “clever” trap we’ve all fallen into. Clever solutions carry hidden costs. Clever solutions commonly ignore the problem. Clever engineering commonly mistakes the effort of implementation difficulty for effort required to solve the problem; it thinks the resistance it feels is the proof that progress is being made against the problem.

There are a few things that I did not consider:

- If each component manages its own loading and error state, then the loading experience on the page could be a little unnerving. Instead of clean loading sequences, users would see a chaotic view of spinners firing simultaneously.

- I failed to analyse the data dependencies. Both components had identical data requirements, but were hitting different endpoints. The platform had evolved and provided a standardised endpoint that Details was consuming, but Tab / Specific Detail was not. Given this convergence, maintaining separate loading states made no sense.

- The fundamental question: does partial rendering actually serve the user? From a resource optimisation standpoint, yes. But does it serve the user’s mental model? Is the users experience of the product dependent upon it making sense as a whole.

Had I done this analysis upfront, I would have implemented state management at the page level. The page represents a single business entity—an item and its manageable aspects. There’s no justification for complex, component-specific loading when we’re fundamentally dealing with a single conceptual unit. It’s a cohesion problem, and I chose the wrong abstraction boundary.